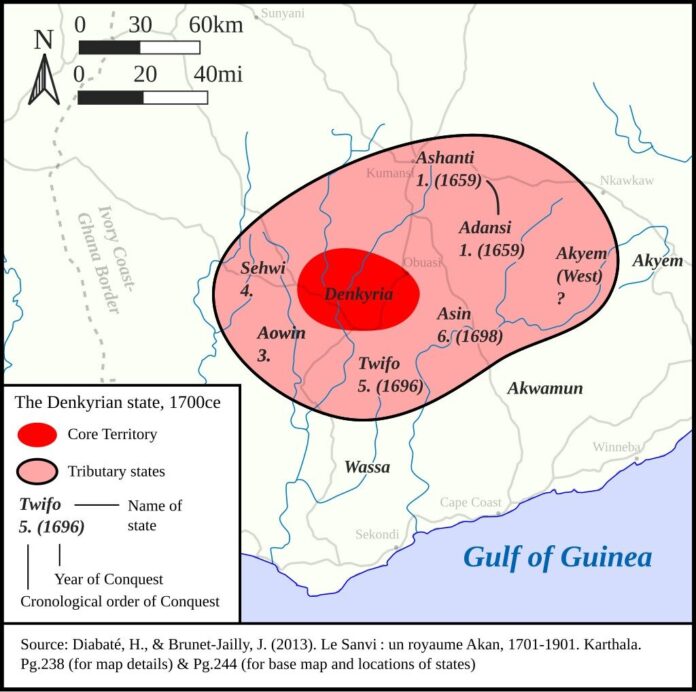

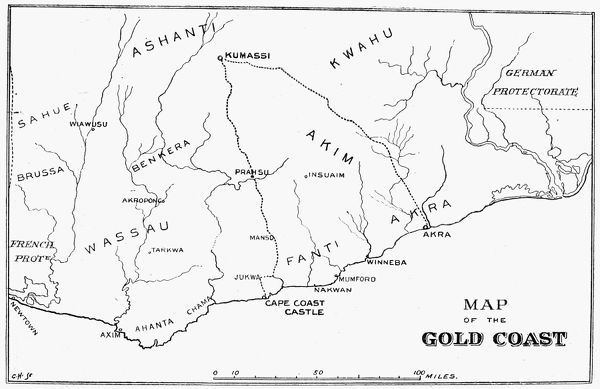

Akan, an ethnolinguistic meta-ethnicity, encompasses diverse peoples united by shared linguistic, cultural, and ancestral origins across modern Ghana, eastern Côte d’Ivoire, and parts of Togo. Speakers of Akan languages within the Kwa branch of the Niger-Congo family include subgroups such as Akyem, Anyi, Asante (Ashanti), Attié, Baule, Bono (Brong), Chakosi, Fante (Mfantse), and Guang; some classifications treat Twi as a distinct yet integral variant.

The Gold Coast in Ghana, from an English newspaper of 1895.

These communities trace their presence to successive migrations between the 11th and 18th centuries, establishing compact settlements in forested and coastal zones.

The Akan economy integrates subsistence agriculture with commercial exports. Yams serve as the principal staple, supplemented by plantains and taro; cocoa and palm oil constitute key cash crops, sustaining trade networks inherited from precolonial gold exchanges.

The Akans (Akanfuo)

Traditional Akan society is organized around exogamous matrilineal clans, in which descent follows the maternal line from a common female ancestor. These clans form hierarchical structures, subdivided into localized matrilineages that constitute the foundational social, economic, and political units.

Villages, typically compact and divided into wards aligned with matrilineages, are further segmented into compounds that house extended, multigenerational families. Governance resides in the village headman, who is elected from a senior lineage, and a council of elders, each heading a constituent matrilineage. The lineage head safeguards the black stools, emblematic vessels uniting the spirits of ancestors (Nananom Nsamanfo) with the living; each matrilineage also venerates its own deities (Abosom) or gods.

The Okyeame institution, embodied by linguists wielding staffs (Okyeamepoma), facilitates diplomacy and counsel, interpreting the unspoken in chiefly deliberations. Drum language, a codified percussive idiom, conveys messages, proverbs, and histories across distances, embedding communal memory in rhythm.

References

- Britannica. (2025). Akan. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Akan

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). Akan people. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akan_people

- Acquah, F. (2017). Reading Hebrews through Akan ethnicity and social identity. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies, 73(3). Retrieved from http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0259-94222017000300016

- Lowes, S., & Nunn, N. (2024). The slave trade and the origins of matrilineal kinship. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 379(1893). Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10799733/

- OpenEdition Books. (n.d.). Elite Succession Among The Matrilineal Akan of Ghana. Retrieved from https://books.openedition.org/etnograficapress/1338?lang=en

- Asante, E. A. (2023). Akan Traditional Religion and Economic Ethics. ResearchGate. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/377753758_Akan_Traditional_Religion_and_Economic_Ethics