Art has always been the language of the Akan. Long before writing, the people spoke through color, shape, texture, and rhythm.

Every carving, cloth, and ornament carried meaning, connecting the seen and unseen world. Akan art was never made only for beauty. It was made to speak, to remind, and to teach.

The Heart of Gold

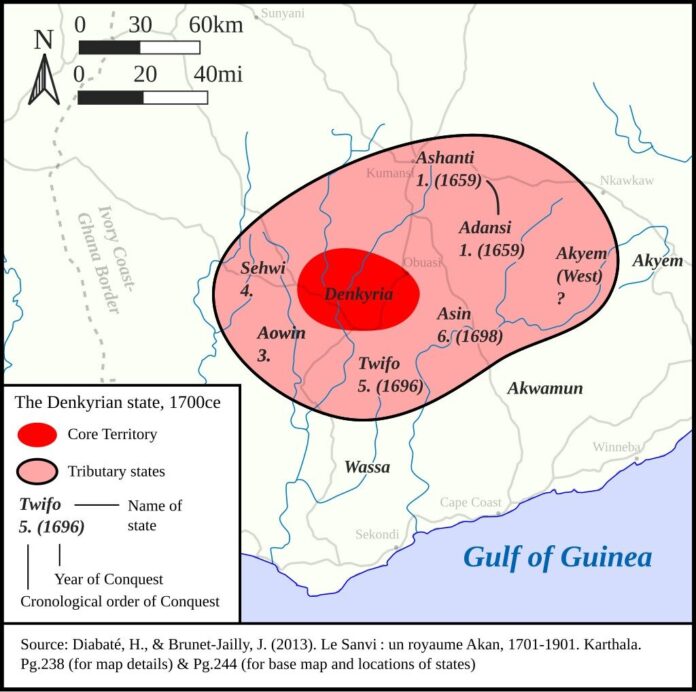

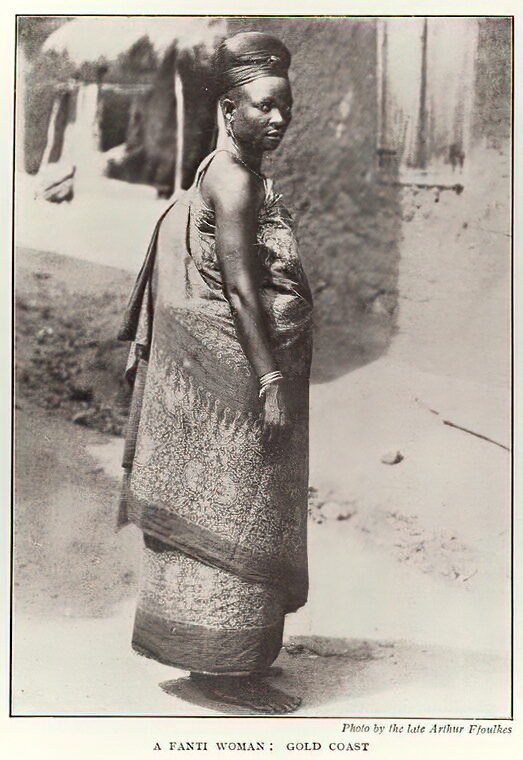

Gold lies at the center of Akan artistry and belief. From riverbeds and forest streams (even today), nuggets were drawn and refined into ornaments fit for kings and queens. Gold represented purity, power, and the eternal presence of the spirit. Among the Asante, especially, goldsmiths were both artists and philosophers.

Using the lost-wax method, they shaped gold dust into rings, bracelets, pendants, and emblems known as abosodee, each distinct & unique, carrying a message.

A crocodile with two heads symbolized shared destiny. A bird in flight holding an egg in its beak spoke of the need to look back even while moving forward. Such designs were not random decoration, but served a key role in the Akan culture as living proverbs cast in metal.

The Golden Stool itself stands as perhaps the greatest expression of Akan artistry. Said to have descended from the heavens, it represents the soul of the then Asante Kingdom. It is never sat upon, for it belongs not to any man or woman but to the spirit of Asanteman.

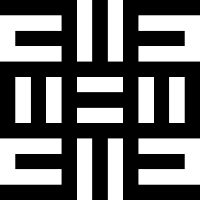

The Loom and the Thread

The loom is another “throne” in the Akan world. Through it, the weaver tells stories in color and pattern. The kente cloth, woven from silk and cotton, is perhaps the most recognized of all Akan crafts. Each design bears a name and meaning.

Adwinasa teaches that all patterns are used up, meaning perfection. Fathia Fata Nkrumah celebrates unity and love.

Weaving is both an art and a meditation. The weaver listens to the steady rhythm of the shuttle as it passes back and forth. In the old days, kings wore kente to mark great occasions, but today it graces weddings, festivals, and graduations across the world.

Through the kente, the Akan philosophy and way of life are preserved and passed on to the current and future generations.

The Voice of the Carver

Wood carving holds sacred value among the Akan. Before cutting a tree, the carver pours libation and speaks to the forest, asking permission from the spirits that dwell within it.

Stools, linguist staffs, and drums are the most revered wooden creations. The stool is symbolic of a person’s soul. When a chief dies, his stool is blackened with soot and stored in the ancestral shrine to honor his spirit. Unless and until a worthy successor claims that stool and is named after the first occupier as a sign of respect, honoring the ancestor who once held reign on that stool.

The linguist staff, carried by the okyeame, bears carved figures that reflect proverbs. One staff might show a hen protecting her chicks, a reminder that a leader must care for his people.

Another may depict two men holding a knife by the blade and handle, showing that peace lies in shared pain and understanding.

Drums, too, speak in the Akan culture. The atumpan, or the talking drum, carries messages across villages. Its rhythm can announce the arrival of a chief, a funeral, or a war.

Even today, the talking drum remains a symbol of communication between the living and the ancestors.

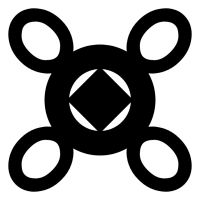

The Adinkra Symbols

Akan art is rich in symbols, known as adinkra. These symbols appear on cloth, pottery, architecture, and even metalwork. Each has deep meaning drawn from proverbs, history, and moral teachings.

The Sankofa bird, turning its head backward while holding an egg, urges the people to return to the past and learn from it. Gye Nyame, meaning “Except God,” proclaims faith and humility. Dwennimmen, shaped like ram’s horns, teaches strength in gentleness.

Adinkra cloth, dyed in deep earth tones, is worn at funerals and festivals. Each symbol printed on the fabric tells a unique story of the wearer’s belief, their mood, and/or conveys a specific message.

The Artist and the Spirit

In Akan belief, art is never separated from the spiritual. The artist is a vessel through which the ancestors speak, and ancestral knowledge is passed onto the living. Before creation begins, rituals are performed to invite good fortune and clarity.

This sacred view of art has preserved the Akan aesthetic across generations. Even as modern artists experiment with new materials and global influences, the roots remain strong.

Central themes of harmony, respect, and continuity.

Modernity & Revival

Today, Akan art stands proudly in museums, galleries, and marketplaces around the world. Yet its truest form still lives in the villages and towns of Ghana, where craftsmen and women continue to weave, carve, and cast with devotion.

Modern Ghanaian artists draw from these traditions to tell new stories about migration, identity, and freedom. And today, the Kente has been officially identified as originating from Ghana, i.e., the Akans, and is a source of pride as recognition of this key loom is displayed on the global stage.

Through sculpture, painting, and digital media, they extend the Akan conversation into the future. An art that is language, memory, and spirit made visible to its people.