The Ashanti Kingdom took root in the forest heart of modern Ghana during the 18th century, lasting for centuries as a hub of structured rule and cultural depth. Kumasi served as the heartbeat, the seat of the great leaders of Asanteman, where they showcased their power through art and unity. This mix of force and creativity is what made (and still makes) the Ashanti a key player in West Africa, trading gold while defending their cultural ways.

The Kingdom of Gold

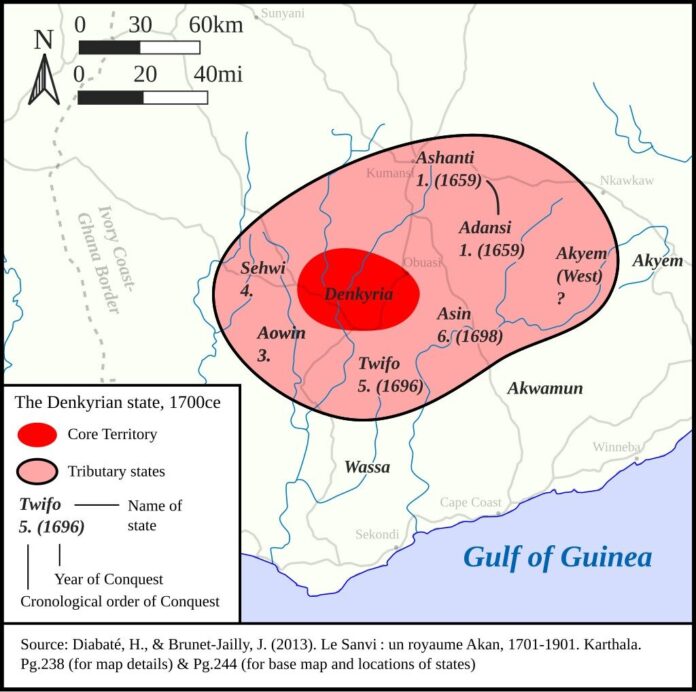

The Ashanti traces its origin to the late 1600s, when Akan groups paid heavy tribute to the Denkyira. Osei Tutu, emerging as a unifying force in the 1670s, rallied chiefs against this control. With advisor Okomfo Anokye, he forged a confederacy, symbolized by the Golden Stool, said to descend from the sky as a sign of divine favor upon the newly established. This stool, never sat upon, embodied the nation’s soul and bound clans in loyalty.

The decisive Battle of Feyiase in 1701 shattered Denkyira rule, freeing Ashanti to claim gold fields and trade routes. Opoku Ware, Osei Tutu’s successor from around 1720 to 1750, pushed borders outward, covering much of Ghana through skilled warfare and alliances. Firearms from European coastal traders boosted their edge, turning Ashanti into a power that supplied gold, ivory, kola nuts, and captives across Saharan and Atlantic networks.

Military Organization and Conflicts

Ashanti forces, led by generals called Kronti, formed a disciplined army that could rally thousands swiftly. Warriors crafted their own arms, blending local ironwork with imported guns, and protected vital gold mines. This strength fueled expansion but drew colonial friction.

The Anglo-Ashanti Wars, spanning 1824 to 1900, marked fierce opposition to British encroachment. Early victories, like the 1824 defeat of a British unit, showed Ashanti resolve. Yet superior weaponry shifted tides; the 1874 Sagrenti War, named for British General Garnet Wolseley, saw Kumasi burned and treasures looted, many still held in European museums today.

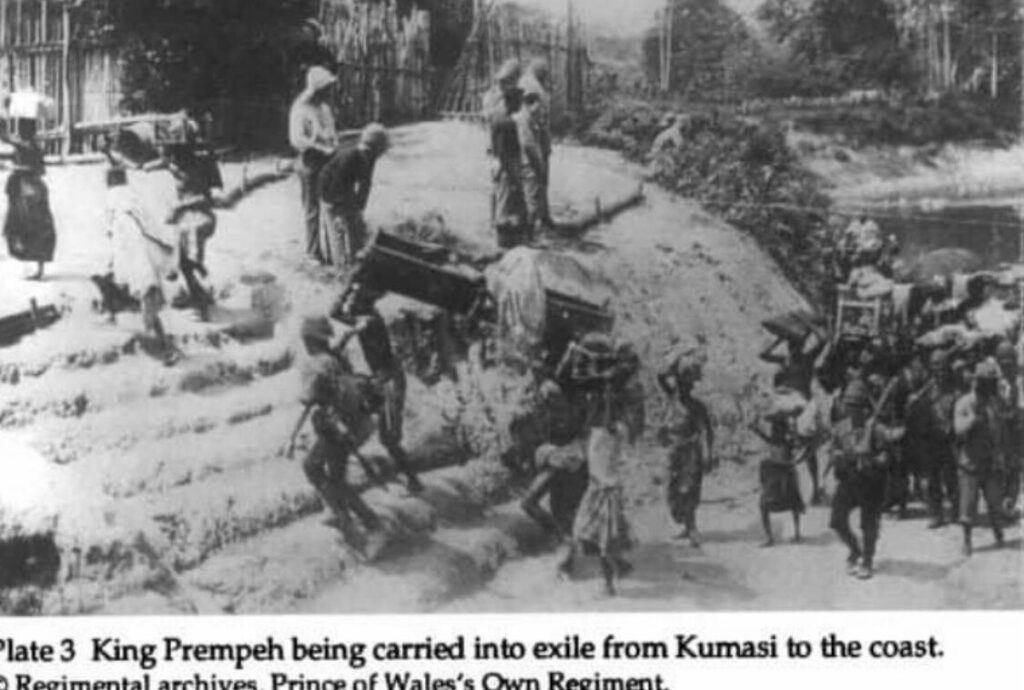

King Prempeh I’s 1896 exile to the Seychelles followed his refusal to yield sovereignty. The 1900 War of the Golden Stool erupted when British Governor Frederick Hodgson demanded the stool, igniting revolt under Queen Mother Yaa Asantewaa of Ejisu.

Her call, “If the men of Ashanti will not go forward, then we will”, rallied fighters in a final stand, though she too faced exile.

Goldsmithing and Craft Traditions

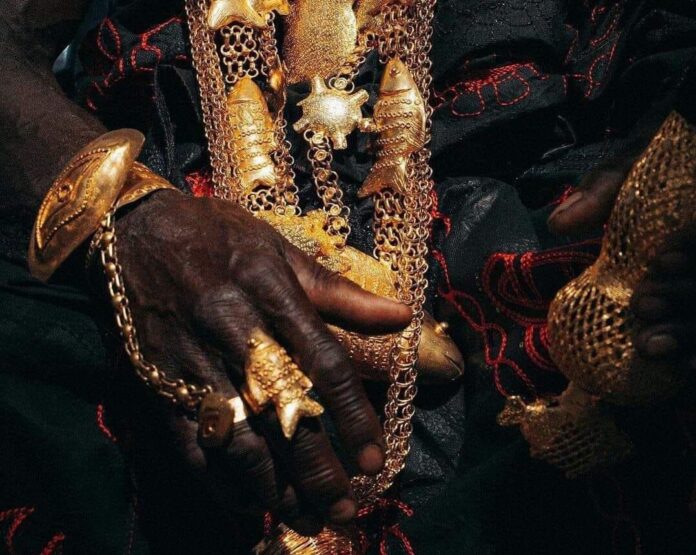

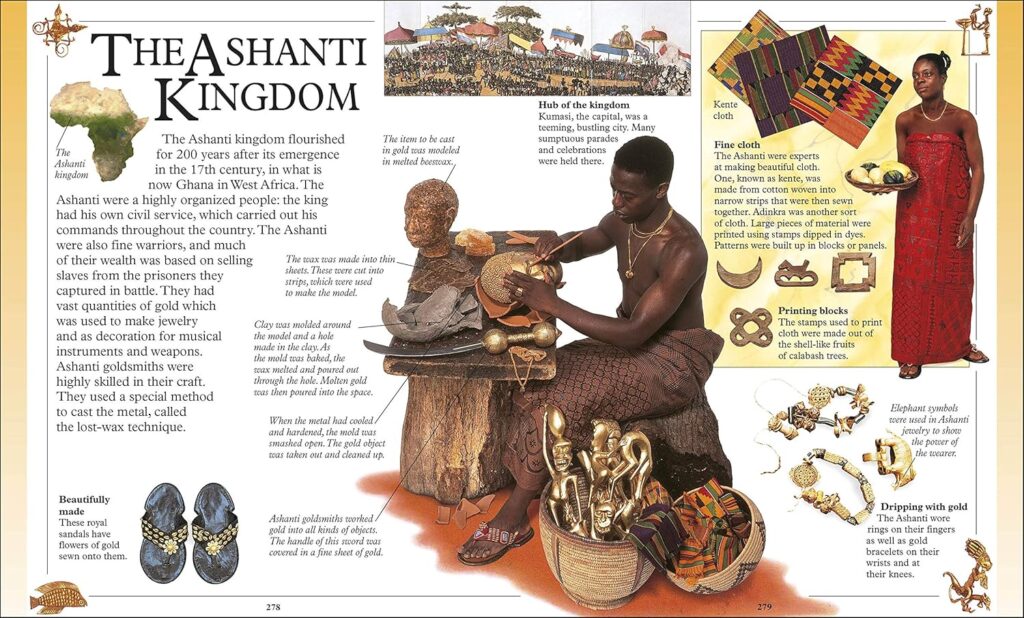

Gold underpinned Ashanti wealth and artistry. Miners panned rivers for nuggets, which guilds shaped into regalia using lost-wax casting: Wax models coated in clay, heated to drain the wax, then filled with molten gold for items like soul-washer badges and elephant pendants symbolizing power.

Jewelry displayed status in Asanteman; rings, bracelets, and ankle bands for elites, even sandals with gold accents. Craftsmen also forged swords and bells, blending utility with symbolism in royal displays.

The Ashanti Way

Weavers excelled in kente cloth, spun on narrow looms into striped panels sewn for garments. Patterns drawn from the lessons of life, conveying proverbs silently. Adinkra stamps, cut from calabash and dyed, printed motifs on fabric for resilience or faith, worn in ceremonies.

Akwasidae gatherings every six weeks: Drummers beat messages on talking drums, dancers in adinkra swirled through crowds, chiefs paraded in gold-heavy kente with staffs aloft. The Ashanti Way of Life needs to be experienced to be understood. Wherein Libations were poured amid chants, blending joy with ancestry respect and worship … All under the Golden Stool’s shadow.

Markets like Kejetia (which exists today) traded these crafts, sustaining an economy of yams, cocoa, and palm oil alongside gold.

Colonial rule disrupted but did not erase Ashanti ways. Prempeh I returned in 1924; the 1935 Asante Confederacy revival under Prempeh II restored traditional governance. Today, Asantehene Otumfuo Osei Tutu II, the one they aptly call Opemsuo, enthroned in 1999, promotes education and peace, while calls continue for looted artifacts to return to whence they belong. Museums like the one in the Manhyia Palace preserve this history, linking the past to Ghana’s present.

Asante Yɛ Oman Ampa!

Quick Facts

Date: 1701–1900

Key People: Osei Tutu; Okomfo Anokye; Yaa Asantewaa; Prempeh I; Garnet Wolseley

Related Topics: Golden Stool; Anglo-Ashanti Wars; Akan states

Related Places: Kumasi; Ghana; Gold Coast