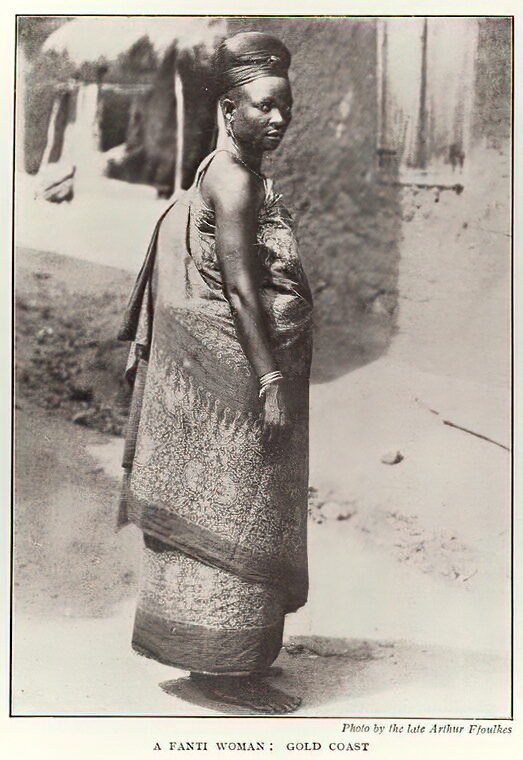

By the early 1900s, the Akan world was changing fast. Colonial rule had altered old systems, but it could not erase memory.

Chiefs who once ruled vast territories now worked within the colonial structure, yet remained the keepers of ancestral knowledge. Through oral tradition, they preserved the essence of Akan governance, the belief that leadership is service, not domination.

As schools opened and cities grew, a new generation of Akan youth found themselves walking between two worlds: one rooted in tradition, the other shaped by European education.

It was from this blend that Ghana’s early nationalist leaders emerged, men and women who carried both the wisdom of the stool and the influence of European education.

The Akans’ Role in the Birth of Ghana

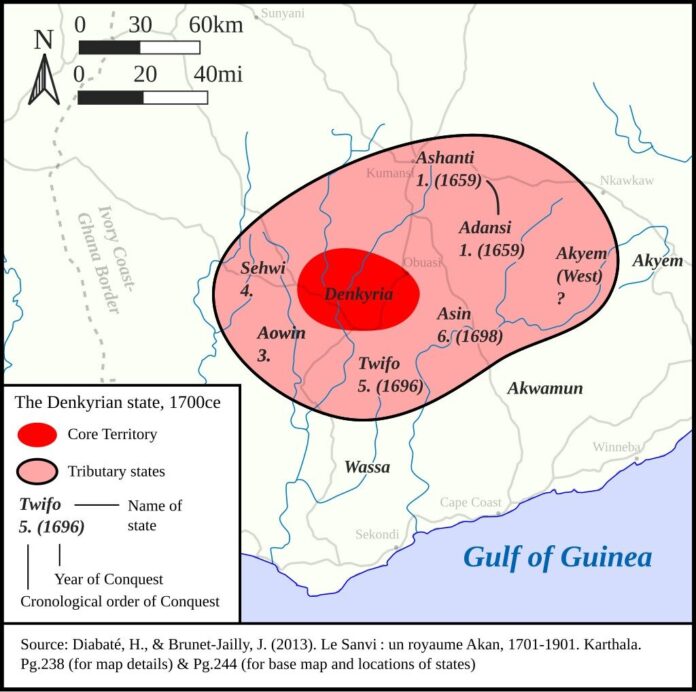

Among those who led the independence movement were many of Akan heritage. These were thinkers, organizers, and chiefs who envisioned a united nation.

The words of Kwame Nkrumah carried echoes of Akan communal ideals. His dream of unity and self-reliance resonated deeply with Akan philosophy, which teaches that a tree with many branches stands stronger than one alone.

The years after independence saw a revival of cultural pride among the Akan. The Chiefs regained new relevance as custodians of heritage.

Festivals such as Akwasidae, Odwira, and Bakatue grew in national prominence, becoming centers for the young to reconnect with their roots.

The kente cloth, once reserved for royals, became a symbol of African dignity across the world. Its patterns told stories of patience, unity, and endurance.

Adinkra symbols, once used only in sacred rites, found new expression in modern design, fashion, and art.

This fusion of the ancient and the modern became the heart of Akan identity in postcolonial Ghana. It showed that tradition need not fade in the face of progress, but rather, could guide it.

Akan Leadership in Modern Ghana

In the decades after independence, Akan chiefs and leaders continued to play key roles in shaping the nation.

The Asantehene, Okyenhene, and other paramount chiefs became voices of reason during times of political turbulence. They reminded leaders and citizens alike that no stool is greater than the people who raise it.

Today, the Asantehene Otumfuo Osei Tutu II stands as a bridge between history and the present. His work in education, peace building, and heritage preservation carries forward the same spirit of Osei Tutu and Okomfo Anokye, with a vision suited for a modern world.

Across Akan lands, chieftaincy remains a respected institution.

Akan Influence Beyond Ghana

The Akan legacy goes far beyond modern Ghana’s borders. In the Caribbean and the Americas, descendants of the Akan people carried with them songs, proverbs, and spiritual practices that still exist in communities today.

Words like “Obia,” “Sankofa,” and “Akwaaba” appear in the cultural memory of Jamaica, Suriname, and Brazil, proof that, though enslaved, the Akan spirit could not be erased.

This global footprint has made Akan culture one of Africa’s most recognizable heritages, celebrated for its resilience, philosophy, and artistry.

The Akan Way

Modernity brings new challenges; urban life, migration, and digital culture have changed how younger generations connect to tradition.

Yet the Akan principle of Sankofa, “return and fetch it”, remains as relevant as ever. It reminds people that no matter how far they advance, the wisdom of the ancestors must not be forgotten.

Across Ghana, cultural centers, museums, and schools are reintroducing young people to the stories of the clans, the language of the drum, and the meaning of proverbs.

Elders are working to document oral traditions before they fade, ensuring that the Akan story remains alive for generations yet unborn.

And sites such as this one ensure that, while Independence was a great victory. Preserving the spirit that made it possible is ensured!