With the abusua as the basis, the great Akan states grew, transforming a shared ancestry into powerful nations. What began as small settlements bound by blood and faith became organized societies ruled by chiefs, warriors, and priests. Each state had its own unique culture, shaped by trade, war, and the will of the ancestors.

Unity and Expansion

As the clans spread through the forest belt, fertile lands and abundant gold encouraged them to settle permanently. Villages grew into towns, and some towns eventually morphed into states. The early settlement centers, such as Bono Manso, Begho, and Adanse, became models of political order and economic success from which many clans learnt and emulated.

Chiefs ruled with the advice of their elders, enforcing justice through customary law and spiritual authority. Each community respected the stool as a sacred symbol of power, representing both leadership and the spirit of the people.

The stool upon which sat the king represented service to the community and protection of the lineage. The myth that African cultural institutions were nonexistent before the arrival of the Europeans. Remains just that, for there is unequivocal evidence of structure, culture, and tradition long before the coming of European traders and settlers.

The Bono and Denkyira Influence

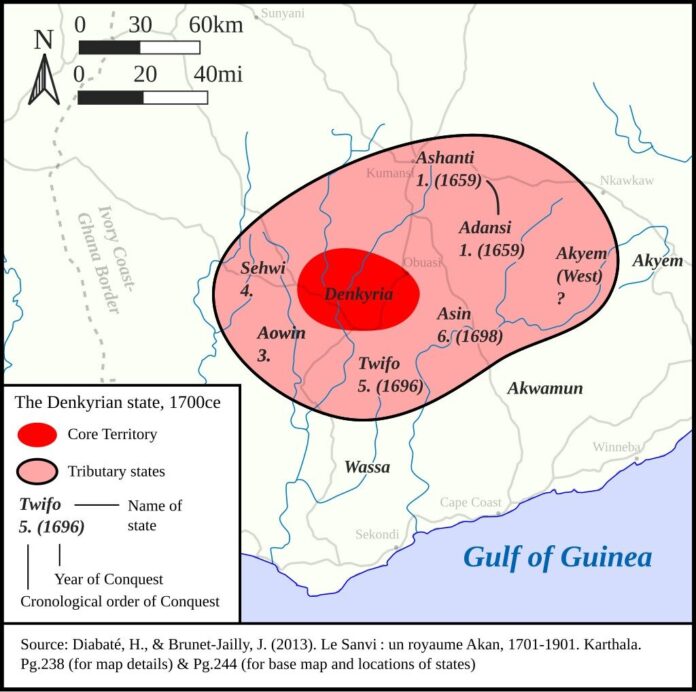

The Bono people, already famous for their gold and trade, were among the first to establish an organized state system. Their success inspired neighboring Akan groups to form their own. Denkyira emerged as one of the most powerful, controlling trade routes and collected tribute from smaller states.

Denkyira’s strength came from its control of gold and its disciplined army.

It became a center of wealth and influence, uniting several Akan groups under its rule. But its dominance also created tension, as other rising states began to resist the burden of tribute and sought their own independence.

The Birth of New Powers

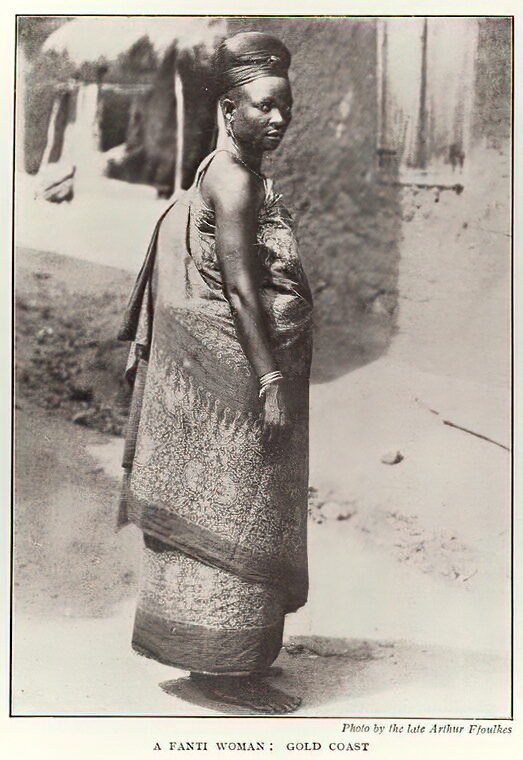

In the east, Akwamu grew into a mighty power, with a focus and mastery over both diplomacy and warfare. Akwamu chiefs expanded their influence to the nearby rivers and plains, reaching even into parts of the coast. To the south, the Fante and Asebu established coastal states that thrived on trade with early European merchants.

These new powers learned quickly how to balance internal unity with their external ambition.

They built alliances through marriage and trade, creating a network of Akan states that shared language and culture but maintained distinct identities. Each state had its own leadership style and ceremony, yet all honored the same ancestral spirit.

The “Golden Age”

By the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Akan civilization had entered its golden age. The gold trade connected them to the rest of Africa and the wider world.

Caravans from the north brought salt, metal, and textiles, while traders from the coast came with goods from across the seas.

With this wealth came growth in art, architecture, and the standard of living. Chiefs built larger courts, blacksmiths crafted intricate ornaments, and priests maintained powerful shrines. Foreign influences inspired new and unique art and culture.

The talking drum [from whence this website’s pseudonym originates] became a messenger between towns, carrying news, commands, and praises across vast distances. The Akan world had come into its own, united by its heritage and belief in Onyankopon, Asaase Yaa, and various deities.

The Rise of Asante

The Asantes, initially formed from alliances among smaller states seeking to break free from Denkyira’s rule, emerged as the Asante Confederacy under the leadership of Osei Tutu and his spiritual advisor, Okomfo Anokye.

They transformed their unity into strength and created a political system that bound clans and chiefs together through the sacred Golden Stool. The stool, said to have descended from the heavens, was a symbol of the soul of the entire nation. It gave the Asante not just a government, but a shared identity rooted in spirituality and loyalty. This will prove to be a uniting bond that led the Asantes through their darkest hours.

The victory over Denkyira at the Battle of Feyiase marked the dawn of a new era.

Asante became the most powerful Akan state, expanding its borders through war, trade, and diplomacy. Its success reshaped the political map of the region and established a legacy that has proudly stood the test of time to this day.

Governance

The Akan states thrived because of a governance system built on balance. The chief ruled, but never alone. The council of elders, the queen mother, and even the stool carriers all played crucial roles in maintaining justice and stability.

Decisions were made through consensus, and every leader was accountable to the people and the ancestors.

This sense of shared responsibility became the central theme upon which the Akan political philosophy and structure were formed, a tradition that valued dialogue, unity, and shared wisdom.

Legacy

The rise of the Akan states marked a turning point in West African history.

Even today, the structure of chieftaincy and the reverence for the stool remain living symbols of that golden age.

From Bono to Asante, Akwamu to Fante, the spirit of the ancestors continues to guide the Akan people.