When the white sails of European ships appeared along the Gulf of Guinea, they brought not only trade but also a slow, creeping power that would reshape the existing power structure of the Akan people.

For what had begun as a partnership in commerce soon turned into a struggle for freedom, as the Akan states faced the encroaching reach of European colonial ambition.

Early Encounters and Trade Relations

The Akan had long been traders. Their gold had reached the markets of North Africa through the ancient trans-Saharan routes long before the arrival of the Portuguese in the fifteenth century.

When the Europeans came, the Akan saw opportunity. They exchanged gold, ivory, and slaves for guns, cloth, and salt.

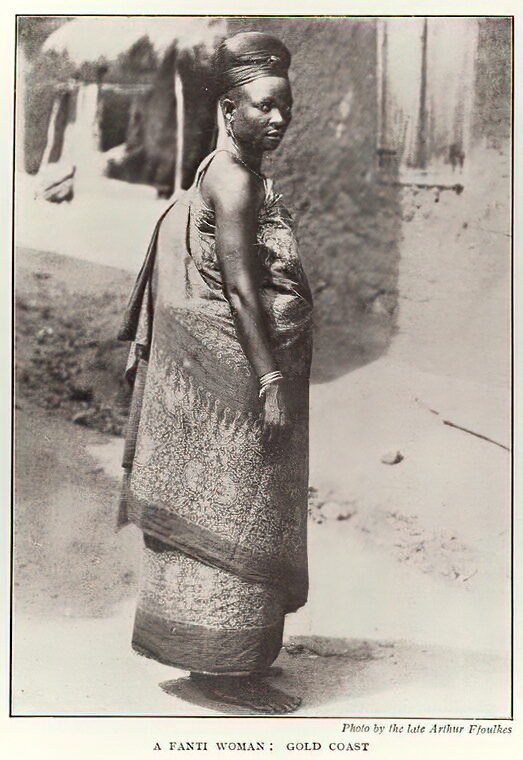

Coastal towns like Elmina, Axim, and Cape Coast flourished. The Fante, with their access to the sea, became skilled middlemen, linking the inland Akan states with European merchants.

But behind this trade, new motives began to unfold. Why trade when direct control could be established?

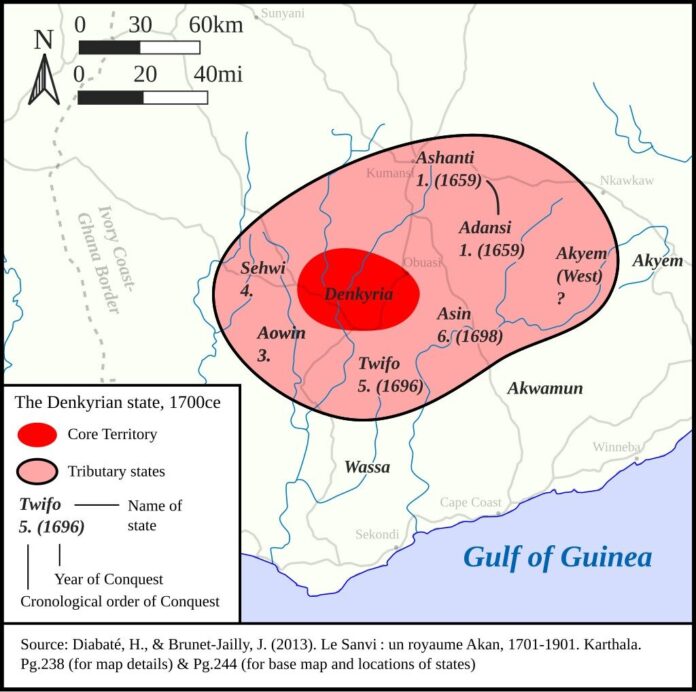

Tensions Among Akan States

As trade with Europeans grew, rivalries deepened among the Akan states. The Fante, supported by the British, often clashed with the inland Asante over control of trade routes.

What had once been an Akan world united by shared language and ancestry became fractured by the politics of foreign influence.

The British saw an advantage in these divisions. They armed coastal allies and spread treaties that slowly eroded the independence of the inland states.

Yet the Akan spirit was not easily broken. Every attempt to impose authority met resistance, sometimes fatal.

The Fall of the Asante Empire

By the mid-nineteenth century, British power along the coast had solidified. Their eyes turned toward the interior, where the Asante Empire still stood firm. The Asante, determined to protect their sovereignty, refused to submit to British control.

A series of wars erupted: fierce, costly, and unforgettable. The 1874 expedition led by Sir Garnet Wolseley marched deep into Kumasi, burning the royal city and looting its treasures.

Though the Asante army fought valiantly, the loss marked the beginning of a new phase, where diplomacy and survival replaced expansion and conquest.

But the Asante spirit refused to fade. King Prempeh I, ascending the Golden Stool, refused to sign away his nation.

His courage led to his arrest and exile in 1896, a humiliation that burned deep in the hearts of his people.

The War of the Golden Stool

In 1900, when the British governor Frederick Hodgson demanded to sit on the sacred Golden Stool, he committed sacrilege. To the Asante, the Stool was no mere symbol; it was the essence of the people, said to contain the spirit of all generations, past, present, and unborn.

At that moment, the silence of the men was broken by the voice of a woman. Queen Mother Yaa Asantewaa of Ejisu rose in defiance, declaring that if the men feared to fight, the women would rise in their place.

Her leadership sparked the War of the Golden Stool, a final, desperate stand for freedom.

Though the war ended in defeat, its legacy remains eternal. The courage of Yaa Asantewaa remains a pillar of not just Asante but also Akan identity.

Colonial Rule and Cultural Resilience

With the fall of the Asante power, the British consolidated their rule over the Gold Coast. They imposed new laws, taxes, and systems of governance that often clashed with Akan traditions.

Chiefs were stripped of authority, and European education sought to reshape the worldview of the young.

Yet even under colonial rule, the Akan spirit endured. Festivals, proverbs, and ancestral rites continued in secret or in modified forms.

Chiefs remained symbols of unity, guiding their people through a time of cultural transformation.

And even as new religions and customs spread, the people preserved the essence of their identity through language, art, and ceremony.

Seeds of Independence

By the twentieth century, the winds of change were stirring across Africa. Educated elites, many of them Akan, began to question the legitimacy of colonial rule. Nationalist movements grew from the very lands that had once birthed empires.

The dream of freedom found new voices; teachers, priests, traders, and chiefs who carried forward the same spirit that once inspired Yaa Asantewaa, Kwame Nkrumah being the most notable.

The Akan contributed profoundly to the political awakening that would one day lead to Ghana’s independence.

The struggle was no longer fought with muskets but with ideas. The same determination that had resisted colonial soldiers now resisted colonial governance. The Akan, once again, stood at the center of history.

The colonial era tested the Akan people more than any other time in their history. Yet it also revealed the depth of their resilience.

Through loss, exile, and foreign domination, they never surrendered their sense of identity.

The Akan remembered who they were. And when independence finally came in 1957, it was not just a political victory but also a spiritual restoration of all that had been fought for since the first day a foreign ship touched Akan shores.