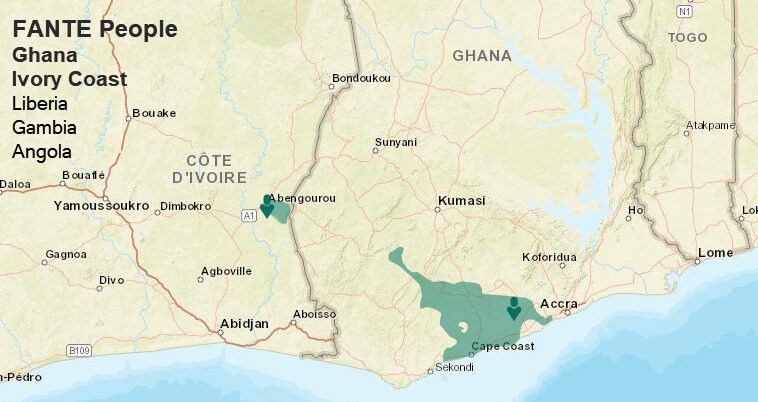

Along the southern stretch of what is now Ghana, the Akan people founded new settlements. This region became home to the Fante, Akyem, Assin, and other southern Akan groups who would shape the destiny of the coast for centuries to come.

The Coast

Long before the first European ships appeared, the southern Akan had already mastered the art of coastal exchange. They traded salt, fish, and woven goods with inland kingdoms in return for gold, ivory, and kola nuts.

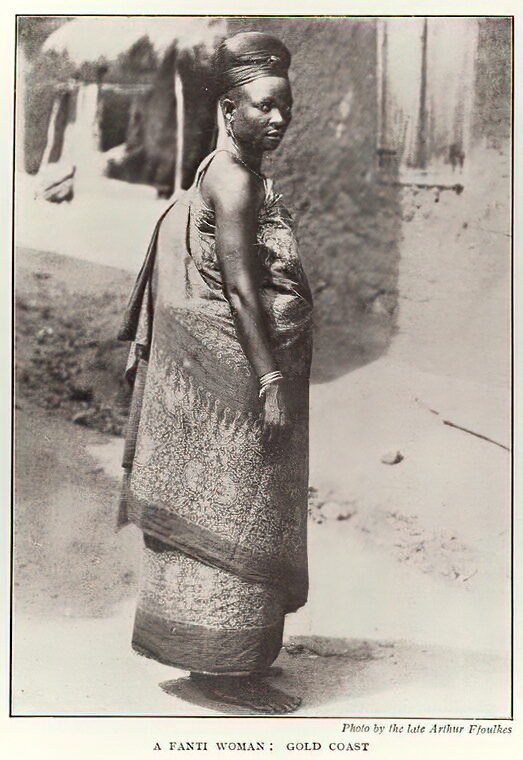

The Fante, whose lands stretched from Mankessim to Cape Coast, became skilled navigators and diplomats. They learned to deal with foreign traders while protecting their autonomy.

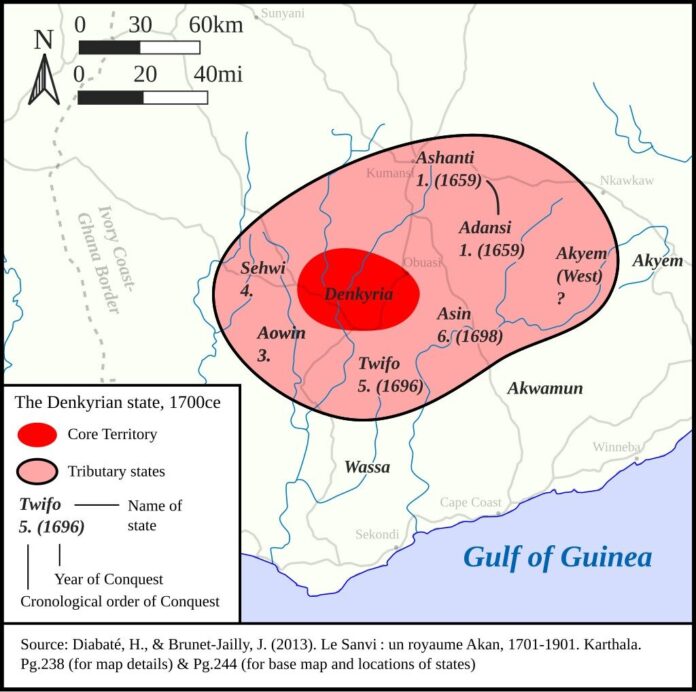

The Akyem and Denkyira to the east and north maintained strong ties with these coastal kin, ensuring that trade between forest and sea flowed smoothly.

The fifteenth century, however, brought new faces to the shoreline. The Portuguese were the first to arrive, building forts like Elmina to control the gold trade. In time, the Dutch, British, and Danes followed, each vying for influence along the coast. The Akan saw them as what they initially portrayed, trading partners.

The Fante, especially, became brokers between the foreigners and the inland kingdoms. They supplied gold, ivory, and, in darker times, captives for exchange.

Through this trade, towns like Anomabo, Elmina, and Cape Coast flourished. Wealth flowed in, but then so did tension.

The Rise of the Fante Confederacy

As European competition grew, so too did the need for unity among the southern Akan. In the eighteenth century, the Fante Confederacy emerged as a loose alliance of coastal states. Led by chiefs and guided by councils, it sought to regulate trade, protect independence, and balance relations with both the British and the powerful Asante inland.

The Fante Confederacy was a symbol of Akan adaptability. It blended ancient clan governance with new diplomatic strategies suited to a changing world.

Chiefs met in council to decide matters of war, trade, and taxation, showing the communal spirit that lay at the heart of Akan politics.

Though the Confederacy eventually fell under British pressure, its legacy endured as one of the earliest examples of organized self-rule along the coast.

Of Trade and Culture

The southern Akan towns became crossroads of cultures. The markets of Cape Coast bustled with goods from every direction: gold and kola from the north, salt and fish from the sea, and textiles from local looms.

The sound of drummers and the chatter of traders filled the air as foreign merchants haggled in pidgin and foreign tongues.

Missionary schools soon followed the forts, bringing new forms of learning. The Fante were among the first to adopt literacy, blending it with traditional education. From these early schools came many of the thinkers who would later shape Ghana’s path to independence.

Despite colonial manipulation, the coastal Akan maintained pride in their identity. They built stone houses beside ancestral shrines, attended church while honoring their stools, and wore kente beneath European coats.

The Akyem, the Eastern Trade Routes & Colonialism

Further east, the Akyem states of Abuakwa, Kotoku, and Bosome played their own role in southern Akan history. Sitting between the Asante hinterlands and the coastal plains, the Akyem became vital in controlling trade routes.

Their leaders valued autonomy as fiercely as their northern cousins.

When the Asante expanded in the eighteenth century, the Akyem fought to maintain their freedom, sometimes allying with coastal powers, sometimes standing alone.

As the nineteenth century unfolded, the British tightened their hold on the coastal forts. Treaties signed under pressure chipped away at the authority of local chiefs. By the late 1800s, Cape Coast had become the seat of British administration, while the Fante and Akyem grappled with new realities of foreign governance.

The southern states also became the birthplace of Ghana’s first educated elite. Writers, teachers, and traders from these regions helped shape Akan ideals, leadership, and wisdom into the modern age.

The Legacy of the Southern Akan

Today, the forts that once symbolized foreign control now stand as museums, their stones speak of both pain and resilience. The festivals of the Fante, such as Oguaa Fetu Afahye, continue to celebrate unity and pride in their ancestry.

Their story is not one of mere submission but also of endurance. Through trade, conflict, and adaptation, they ensured the survival of their culture. While some modern historians will argue against the route by which some of these Southern States gained wealth and power. The sustenance of their way to this age remains unquestioned amidst great change and upheaval.